Background

Background

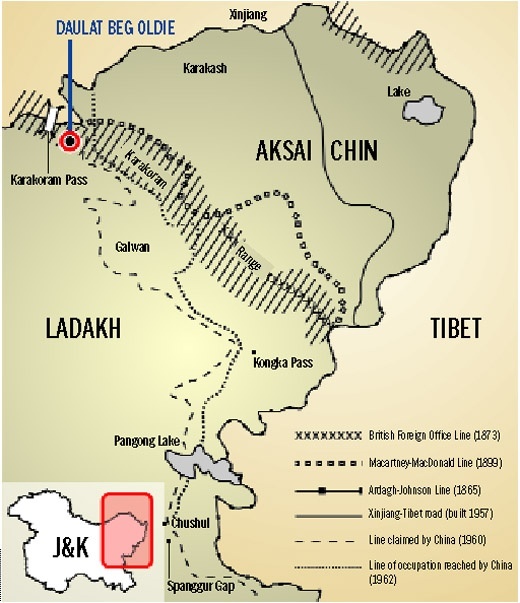

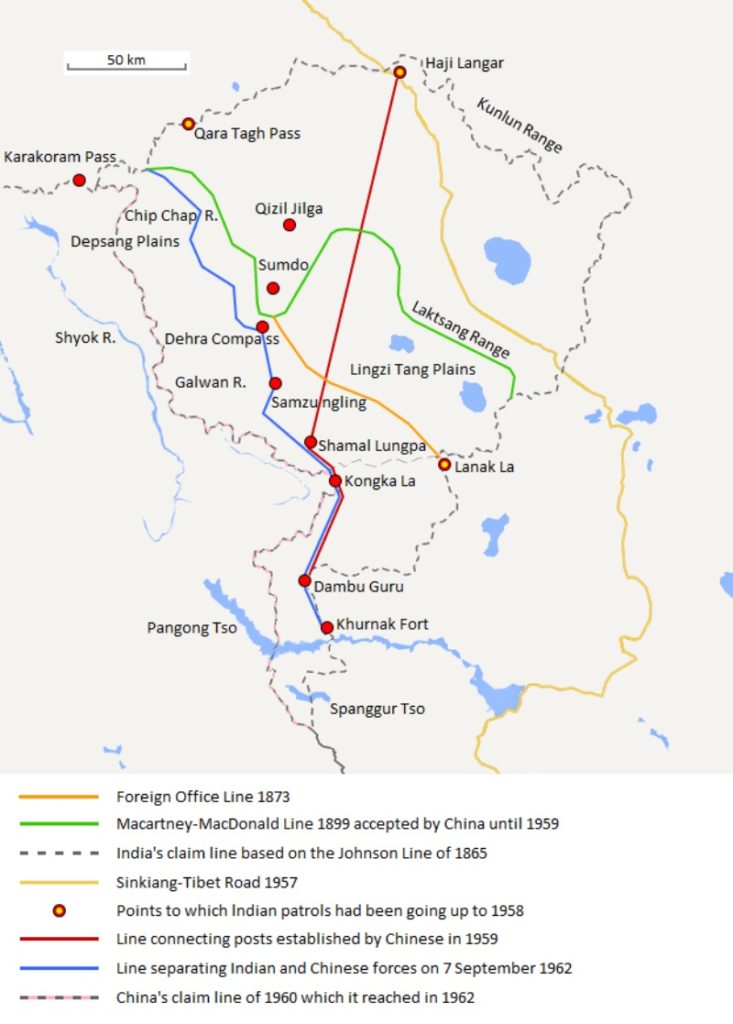

India’s northern border, including Aksai Chin of Ladakh, was governed by the Treaty of Chushul signed between the Tibetans and Gulab Singh (ruler of Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir) in 1842. Accordingly, in 1865 the British mapped the Ardagh-Johnson boundary line along the natural barrier of Kunlan mountains, including Aksai Chin in India.

Aksai Chin bordered the ancient countries of East Turkestan and Tibet. East Turkestan was forcibly captured by China in 1878, after over 2 crore local people had lost their lives due to this violence. China renamed East Turkestan as Xinjiang. The region exchanged hands many times between local Uyghur Muslims and the Chinese. However, India’s boundaries remained unchallenged even in 1893, when senior Chinese official Hung Ta-chen at St Petersburg provided an official map which coincided with the Ardagh-Johnson line and placed Aksai Chin in British-Indian territory.

Later George Macartney, the British Consul-General positioned in Chinese-occupied Xinjiang, re-mapped the boundary line along the Karakorum Mountains to create a buffer between British-India and the advancing Russians. Sir Claude MacDonald, the British minister in China, proposed this Macartney-MacDonald Line in 1899 to the Qing dynasty, China’s last imperial dynasty. China neither signed nor accepted the document, nor gave any response, because their own claim of East Turkestan (Xinjiang) was without any foundation. Immediately, the British reverted back to the Ardagh-Johnson line. From 1917 to 1933, the official ‘Postal Atlas of China’ showed Aksai Chin in India and the boundary as per the Ardagh-Johnson line. The ‘Peking University Atlas’ also put the Aksai Chin in India in 1925.

Hu Shih (Chinese ambassador to the USA from 1938-42) said:

“India conquered and dominated China culturally for 20 centuries without ever having to send a single soldier across her border.”

China forcibly recaptured East Turkestan (Xinjiang) in 1949. Post-1950, the Chinese Communist Party stated that Aksai Chin was a disputed territory, falsely claiming that the British had unilaterally mapped it in India. But, China’s claim was illegal, as India’s claim was based on historical and documented facts i.e. Treaty of Chushul of 1842, the Ardagh-Johnson boundary alignment of 1865 and several Chinese official documents.

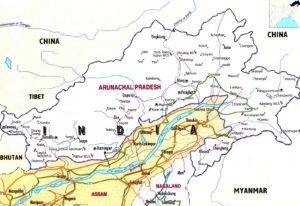

In northeastern India, at Arunachal Pradesh (earlier known as NEFA i.e. North East Frontier Agency), the British had negotiated the McMahon boundary line with Tibet in 1914. China was never there in the picture, either before 1914 or during this agreement. After China forcibly annexed Tibet in 1950, they rejected this McMahon boundary line too.

1950-55

When China attacked Tibet in 1950, USA offered help to India to defend Tibet. Their estimate was that India had only to send a brigade of troops to Tibet, and China would have backed off. In fact, Sardar Patel wrote a long critical letter to Nehru, criticizing his Tibet policy and China appeasement policy! This letter is published in the book ‘Himalayan Blunder’ by Gen Dalvi (1969) AND also ‘Between the lines’ by Kuldip Nayar (1969).

Immediately, the deceitful Chinese refused to accept McMahon line as the international boundary at Arunachal Pradesh, stating that it did not recognize the treaty signed by Tibet with British-India. Nehru correctly declared that McMahon line is our international border, but curiously failed to say anything about Aksai Chin.

Nehru declined offers from both the superpowers viz. USA and USSR to give India a permanent seat in the UN Security Council between 1950-55. Nehru blundered by offering this seat to China instead, despite China’s open aggression in Tibet. This is as referenced in ‘Nehru – The Invention of India’ by Shashi Tharoor; ‘Nehruvian approach’ by AG Noorani and ‘Not at the cost of China’ by Anton Harder. Nehru also promoted the term ‘Hindi Chini bhai bhai’ in 1954.

1956-58

From 1956, China started building an all-weather motorable 750 km long road connecting Xinjiang to western Tibet, of which 112 km was through Aksai Chin. But surprisingly, Nehru formally complained to China only in 1958 that this was an illegal encroachment into Indian territory. China countered saying this area was of no benefit to India. In reply to Nehru’s letter, China proposed to accept McMahon line in Arunachal Pradesh as the border, in return of keeping Aksai Chin. But this was obviously not acceptable to New Delhi.

Highway construction between Srinagar and Leh was stopped in 1956 due to allegations of corruption. So during the 1962 war, Leh could be approached only on mules or supplies had to be air-dropped.

1959-60

Nehru hid about this boundary dispute to the Parliament till August 1959. He also lied to the Indian Parliament that India had not received any letters from China! India and China had first exchanged letters about the Arunachal Pradesh border in 1954. Nehru changed his official views several times by saying he was quoted out of context, further complicating matters.

Meanwhile, China had taken a decade of tough negotiations but settled on its boundary disputes with Burma (based on the McMahon line), Pakistan (based on the Macartney-MacDonald Line), Nepal, Mongolia and Afghanistan. Secret CIA documents showed that the Burmese Premier had warned Nehru against trusting the Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai.

Mood got worse when Tibetans rose for independence and Dalai Lama fled to Mussourie in India (later he moved to Dharamsala). Nehru visited him immediately in Mussourie and further irritated China.

After a New Delhi summit on border talks in 1960, Zhou Enlai called Nehru an unreliable person who kept changing his stand.

Plight of the Indian army

Indian Army of 280,000 was short by 60,000 rifles, 700 anti-tank guns, 5,000 radio field sets, thousands of miles of field cable, 36,000 wireless batteries, 10,000 one-ton trucks and 10,000 three-ton trucks! Two regiments of tanks were not operational due to lack of spares. Most of the Indian troops were using .303 rifles which had seen action even before World War I (not II). Chinese troops were equipped with machine guns, heavy mortars and automatic rifles. Nehru prohibited import of arms because his Non-alignment image would look bad. He often quoted Gandhi’s ahimsa!

The general altitude on the Ladakh border was 14,000 feet above sea level and patrols had to reach as high as 16,000 feet. Temperatures were arctic and the Indian troops winter clothing was inadequate. Mules were not of much use at that altitude and so supplies had to be air-dropped. The Indian troops had to trek whereas the Chinese troops moved around in trucks. China had already built ammunition dumps and other supplies on their side.

To add insult to injury, it was the general impression that Nehru had an inefficient chamcha as a Defense Minister Krishna Menon, whom both Congress and the opposition parties opposed. Krishna Menon did not implement Gen Thimayya’s recommendations and Gen Kaul was made Chief of General Staff (CGS), though Kaul did not have any combat experience (Kaul was a Kashmiri and may have been a relative of Nehru) This severely affected the morale of the armed forces.

1961

Nehru refused to increase military spending and did not prepare for war. But, he openly talked of war if the Chinese did not withdraw from Aksai Chin. China linked the issue with the McMahon line. Nehru lied in Lok Sabha that India was militarily stronger in the Ladakh sector. To this, Gen SD Verma (Corps Commander) wrote to Krishna Menon’s favourite Gen Thapar (Chief of Army Staff – COAS) that this was incorrect as there were only 2 battalions in Jammu and Kashmir, when the requirement was of 7, AND that the Chinese outnumbered India by at least 5:1. He was forced to resign and his pension was held up for a year! Gen Daulat Singh replaced him as GOC-in-C (Army Commander in Chief) in this sector.

Nehru, Krishna Menon, Gen Thapar and Gen Kaul implemented a flawed ‘Forward policy’, in spite of the Indian army not being adequately equipped. This policy involved moving patrols forward and setting up posts on the land claimed by India, which sometimes happened to be behind Chinese posts. This was done with the naive belief that China will not attack a non-violent nation.

Chinese government send a lot of warnings (diplomatic and otherwise) but Nehru dismissed them as bluff. For all his loyal affection to Nehru, Krishna Menon wrote of him ‘Nehru lets himself be edged bit by bit into a situation from where escape is difficult. He cannot be acquitted of failure’.

USA’s President John F Kennedy after meeting with Nehru in Washington DC in November 1961, said that it was the worst head of state visit and it was like trying to grab something in your hand only to have it turn out to be just fog.

On 5 December 1961 in Rajya Sabha, Nehru had the nerve to state that not a blade of grass grew in Ladakh, so India must not fret about it!

Mid 1962

Ambassador of India to the USA, BK Nehru (cousin of Jawaharlal Nehru) said that the Indian army was badly equipped and could not ensure security, thus contradicting repeated assurances by Nehru to the Lok Sabha. Nehru withdrew the Indian ambassador to China but all throughout the war maintained that diplomatic relations must be maintained.

In July 1962, Gen Daulat Singh who was in charge of the Ladakh area wrote to the Army Headquarters (HQ) about the enormous numerical superiority of the Chinese and the helplessness of the Indian army with the reference to supplies. This was because we were anchored on lower ground due to the dropping zones, and the Chinese army was at a greater altitude. He requested that the forward policy be suspended OR a division of 4 brigades be added. He was ignored. It was inexplicable that Nehru, the leader of a nation would not reinforce troops where needed.

Sep 1962 – the trigger in

Sep 1962 – the trigger in

Arunachal Pradesh

The plight in Arunachal Pradesh was the same. Posts were set up in remote locations. There were no roads here and even air dropping supplies was not possible due to the terrain. The Chinese had all-weather roads on its side and their troops were acclimatized at that altitude. The geography on the Indian side had jungles, mountains, 300 feet deep valleys. Ropes and bamboo suspension bridges were used, which even mules could not cross!

A forward post was setup at Dhola/ Thag La ridge. A border line drawn on the map corresponded to a few kilometers on the actual ground. The Indian army officers suspected that the post may have been North of the McMahon line (in Chinese-occupied Tibet, not in India). The official minutes of their meeting with the Defense Minister Krishna Menon were never noted down, but later reported in newspapers and a few books.

From the nearest road at Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh, this Dhola post was a 6 days uphill trek, if there were no landslides. And the nearest airbase in Tezpur in Assam was a few days away from Tawang. Whereas for the Chinese it was 3 hours from their nearest road, which was constructed to carry 7 ton trucks.

The altitude in this area was 13,000 to 16,000 feet above sea level, and since winter was approaching proper clothes and shoes were required. But the Indian troops were given a cotton uniform with a thin sweater to guard against the wind. Only 30% of air dropped supplies reached the troops, as the parachutes used were re-packed and of inferior quality. This was NOT a war. It was suicidal politics!

The Indian troops came face to face with the Chinese at Dhola post, and there was a skirmish on 8 September 1962. It was a ploy of the Chinese to make India provoke the Chinese into a cause for aggression.

Mid October 1962

Again during a skirmish on 10 October, 50 Indian troops were surrounded by over 1,000 Chinese soldiers at Thag La. There were casualties on both sides. Now 2,500 Indian troops and 500 porters stood in Arunachal Pradesh without winter supplies. Indian troops remained outnumbered by at least 20:1. Gen Umrao Singh of XXXIII Corps suggested that the troops be withdrawn to 3 km south of the McMahon line. Suggestion was ignored and he was removed.

But, Nehru told journalists that in Arunachal Pradesh, the advantage was with India. Thus, he misled the public which led to their expectation of prompt and decisive action against an allegedly inferior Chinese force.

Gen Kaul (Nehru’s cousin) who was on leave from September during the crisis, reached Dhola post to take charge. Kaul immediately claimed of medical pulmonary trouble and withdrew to Tezpur (Assam) on 17 October, and then Delhi. He did not go to a hospital, but went home!

Gen Dalvi made his last of various numerous requests to re-group troops on 19 October. When ignored, he resigned as a last resort.

The actual war starts on 20 October 1962

The actual war starts on 20 October 1962

On 20 October 1962, the war started as China attacked Indian troops on 2 fronts at Arunachal Pradesh and Ladakh. China issued a false statement that India had launched a full scale attack.

In Ladakh, the Chinese faced fierce resistance at Daulat Beg Oldi, near the entrance to the Karakoram Pass; secondly, south of Pangong Lake at Chushul; and thirdly at the head of the supply road down to Leh. Major Dhan Singh Thapa and his small team of about 30 men of the 1st battalion of the 8th Gorkha Rifles Regiment were at Pangong Lake. On 20 October 1962, they were surrounded from 3 sides by about 600 Chinese soldiers. The devious Chinese made an announcement that the Nepalis should not take India’s side, but the Gorkhas offered fierce resistance. After all, blood is thicker than water. The Gorkhas withstood 3 rounds of fierce Chinese attacks. The Chinese had to call in tanks to finally overcome this post. Major Dhan Singh was later honoured with India’s highest gallantry award, the Param Veer Chakra.

China had used 3 divisions in Arunachal Pradesh. Holding a position in Tongpeng La area near Tawang, Subedar Joginder Singh Sahnan of the Sikh Regiment faced repeated attacks by the Chinese between 20-23 October 1962. Despite suffering grievous wounds, he refused evacuation. He manned a light machine gun and killed a large number of enemies. Finally better weapons and superior numbers of the enemy prevailed and Singh was martyred. He was posthumously awarded the Param Veer Chakra for his bravery under adverse conditions. The Chinese troops kept penetrating from Tawang to Se La to Dirang to Dzong to Bomdi La AND another division at Walong encircling the Indian troops, which were completely scattered and outnumbered. Arunachal Pradesh was still under Gen Kaul.

The Chinese supplies were stretched and they did not have a proper air force. For some strange reason, Nehru decided not to use the Indian Air Force, to cut off the stretched Chinese supplies lines. This was a strategic blunder and was against the earlier advice given by the Directorate of Military Operations. China halted their attacks on 24 October and Zhou Enlai sued for peace. He was buying time to regroup his forces but Nehru did not understand this. There would be a lull in fighting for around 3 weeks.

USA and UK supported India and offered arms. But, almost all Non-Aligned nations and the Arab world, except UAE, were silent and urged restraint. This hurt Nehru the most, as he always felt he was the leader of the Non-Aligned Movement. USSR blamed Nehru for the conflict.

A group of Congress and Opposition MP approached President Radhakrishnan to remove Menon and Nehru; suspend the Parliament and impose President’s rule. Finally, Nehru accepted US aid on 29 October. However, Nehru kept defending Krishna Menon. But, finally due to pressure from his own cabinet ministers; several Chief Ministers; Members of Parliament and his party-men and the public, Menon was forced to resign only on 7 November.

The fight was even in Ladakh

The fight was even in Ladakh

When negotiations failed, the hostilities re-started on 14 November. India was at a logistically disadvantaged position in Ladakh. But under Gen Daulat Singh, it was an even contest there.

Major Shaitan Singh Bhati was asked to protect the crucial position at Rezang La, a pass on the south-eastern approach to Ladakh’s Chushul Valley air base, as it had an all weather landing strip. Protecting Chushul airfield was vital, if India had to hold on to Ladakh. Situated at a height of 5,000 meters (16,404 feet) above sea level, Rezang La was considered as the toughest combat zones in world, where mere breathing was a big challenge. Major Shaitan Singh Bhati was leading the Charlie Company of only 120 ‘Ahir’ jawans of the 13th Kumaon infantry battalion here.

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of 5,000 to 6,000 soldiers equipped with heavy artillery support attacked Rezang La, early morning at 330 am on 18 November 1962. A crest of the ridge prevented Indian artillery from lending support. The jawans could have retreated, but the company led by Major Shaitan Singh had no such intentions.

They resisted SEVEN waves of fierce Chinese attacks and over 1,300 – 2,000 Chinese lay dead! Major Shaitan Singh and his men had fought till their last breaths. Major Shaitan Singh was honoured with a Param Veer Chakra posthumously. The Chinese had been taught a lesson here.

Un-surprisingly, China decides to withdraw on 21 November 1962

The Indian soldiers remained firmly entrenched between Tawang and Bomdila in Arunachal Pradesh at the Se La pass (named after tribal girls Nura and Sela who helped the Indian army). The Battle of Nuranang at Se La pass began on 17 November 1962 and went on for the next three days. The Indian post was held by the 4th Garhwal Rifles at an altitude of over 10,000 feet above sea level. Soon, only Rifleman Jaswant Singh Rawat survived and continued to fight by firing from different bunkers. The Chinese soldiers thought they were facing an entire battalion! Jaswant Singh with the help of his 2 associates killed over 300 Chinese soldiers. The enemy finally killed Jaswant Singh, but not before he had single-handedly inflicted a severe psychological blow to the huge Chinese army. Indian Army’s reinforcements arrived, thus stopping the opponents further progress. Jaswant Singh was posthumously honoured with a Mahaveer Chakra. He continues to receive promotions as if he is still alive.

Some key events during the war that may have altered the Chinese strategy, making them declare ceasefire unilaterally:

- Wherever the Indian troops had the resources to stand and fight (both in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh), the Chinese suffered very heavy casualties.

- Krishna Menon’s favourite, Gen Thapar (Chief of Army Staff) was replaced by Gen JN Chaudhari, who ordered the Indian troops in Arunachal Pradesh, to take up positions and under any circumstances stop the Chinese.

- Finally, Nehru’s relative Gen Kaul (Chief of General Staff) resigned and was replaced with the efficient Gen Sam Manekshaw! (Nehru offered Kaul the post of Governor of Himachal Pradesh, after the war!)

- Dumping the Non-Aligned Movement, Nehru had requested the US for help, including 12 squadrons of fighter jets. The US did not comply, but they sent an aircraft carrier to the Bay of Bengal.

- The Indian public’s initial reaction of outrage turned to resolution and surprisingly then to optimism and this war came to be seen as a means for the ultimate triumph! Though hurt, the Indian public seemed mentally ready for a long term war!

On 21 November 1962, China unilaterally announced ceasefire and started to withdraw back north of the McMahon line.

Due to Nehru’s false pride, bad planning and horrible leadership, Aksai Chin still remains illegally occupied by the Chinese. India had lost 1,363 valiant soldiers in the fighting and 90% of whom were in Arunachal Pradesh alone. The Chinese certainly lost many more soldiers. YB Chavan became Defense Minister, on the day the war ended. Nehru had finally learnt his lesson at the expense of a nation, and stopped interfering into the internal affairs of the army. The Indian Army became stronger from the experience and started modernizing.

India crush the Chinese in 1967

The deceitful Chinese built many posts, illegally encroaching into Sikkim. China attacked the Indian army on 11 September 1967 at Nathu La pass in Sikkim. Within 4 days, Indians had demolished many Chinese posts and bunkers. The Chinese waved the white flag. But the deceitful Chinese regrouped and attacked Cho La pass, a few kilometres north of Nathu La on 1 October 1967. India again inflicted heavy casualties on the Chinese, forcing them to withdraw 3 km away from the pass. India lost 88 valiant soldiers in these 2 clashes, but China lost 340 of its soldiers. Zhou Enlai and the Chinese army had learnt a bitter lesson, but not for long.

In 1986, Indian troops discovered that the Chinese had occupied the Sumdorong Chu Valley in Arunachal Pradesh. Gen K Sundarji had the Indian troops and supplies airlifted. India soon occupied its peaks including the Hathung La and Longro La ridges. In early 1987, China adopted an aggressive tone. It is worth noting that at exactly the same time, Pakistan occupied the highest point in the Saltoro mountain range overlooking the Siachen glacier. The Pakistanis attacked an Indian post in April 1987 killing many of our soldiers. India immediately initiated a response and evicted the Pakistanis to establish control over the Saltoro mountain range and Siachen glacier by June 1987. A flag meeting was held between the Indian and Chinese troops in August 1987. Under the resolute leadership of Gen K Sundarji, the Chinese aggression was subdued.

More examples of unwarranted Chinese aggression:

- While India was busy crushing the Pakistanis in Kargil in 1999, the devious Chinese further encroached 5-8 km at Pagong Lake in Ladakh

- The Chinese encroached Raki Nala in Depsang in 2013. India quickly replied by building encampments right opposite. The Chinese withdrew

- Later in 2017, Chinese troops tried to encroach at Doklam at the tri-junction of India, Bhutan and Tibet. But they were pushed back by Indian troops

- Latest Chinese encroachment was in 2020 at Ladakh, sadly when the world was busy fighting against the Chinese virus (Covid)

Sources:

- ‘India’s China War’ by Neville Maxwell, foreign correspondent for ‘The Times’.

- ‘Himalayan Frontiers’ by Woodman

- ‘Himalayan battleground’ by Fisher, Rose, Huttenback

- ‘India and the China crisis’ by Hoffman

- ‘The China-India border war’ by JB Calvin

- Google images

- Various Indian government official sources and documents

India’s LRBM (Long range Ballastic missile) Agni V can strike targets as far as 5,000 km away, covering all of China. India’s nuclear triad missiles already inducted into the armed forces, include Prithvi MRBM (mid-range Ballastic Missile), sea-based Dhanush and submarine-based Sagarika. India has surface-to-air missiles like Akash and nuclear-powered submarine Arihant. India also has BrahMos, the fastest cruise missile in the world, with a top speed of 2.8 mach. India’s land-based armed forces are the largest in the world. India’s Air Force and Navy are the fourth largest in the world after USA, Russia and China. The Indian elephant compares quite favourably against the Chinese dragon.

India’s LRBM (Long range Ballastic missile) Agni V can strike targets as far as 5,000 km away, covering all of China. India’s nuclear triad missiles already inducted into the armed forces, include Prithvi MRBM (mid-range Ballastic Missile), sea-based Dhanush and submarine-based Sagarika. India has surface-to-air missiles like Akash and nuclear-powered submarine Arihant. India also has BrahMos, the fastest cruise missile in the world, with a top speed of 2.8 mach. India’s land-based armed forces are the largest in the world. India’s Air Force and Navy are the fourth largest in the world after USA, Russia and China. The Indian elephant compares quite favourably against the Chinese dragon.